A scrum, in rugby, is a tight-knit group of players, literally heads down, working together toward a common goal: regaining possession of the ball.

It's an appropriate analogy for scrum, the eponymous method of software development. The term has been around since the 1980s, when Hirotaka Takeuchi and Ikujiro Nonaka first applied it to product development.

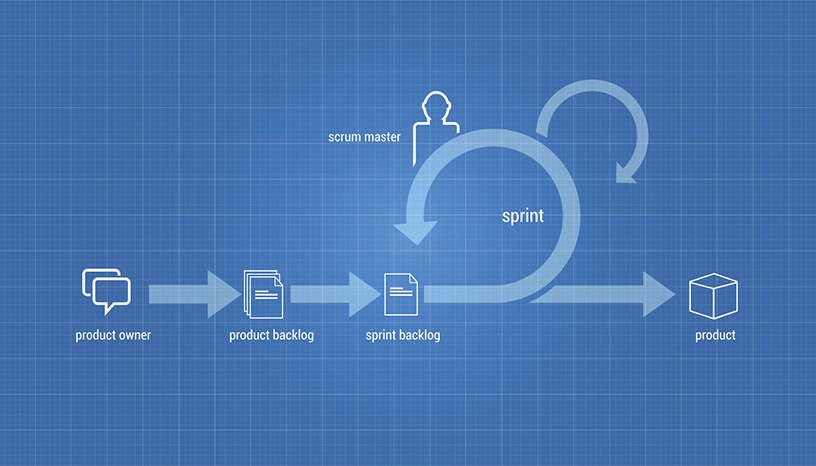

It, and its adherents, consider it continuous, iterative, and incremental. From start to finish, the process is executed by one cross-functional team, moving collectively from one step to the next in lock step. Scrum encourages more team collaboration instead of baton-passing from one person to the next. Continuing with the rugby analogy, a team "tries to go the distance as a unit, passing the ball back and forth." In this way, it overlaps with other flavors of development style, such as agile and kanban. In fact, many categorize kanban and scrum as children in the agile family.

In the agile methods, each iteration of a product is the result of an entire team's efforts: planning, requirements analysis, design, coding, unit testing, and acceptance testing. Scrum, then, is a click down from that.

In scrum, workflow milestones are broken up into sprints. Each sprint kicks off with a planning meeting, where the journey is laid out: tasks and time commitment for each. A sprint is then closed out with a retrospective meeting, where the team reviews progress and lessons learned, as they apply to the next sprint, are identified.

There are notable advantages to this approach. It encourages trust and openness in a team, which paves the way for collaboration and a we vs. I mentality. But for anyone considering it, there are a few pitfalls of moving as a unit.

As we've written about before on the Tracker blog, committing an entire team to a software deliverable can be unsettling on both ends. Though the team huddle keeps everyone on the same page, holding the team accountable for failing to deliver—part of the natural ebb and flow of any project—can act as a "regime of terror."

Though scrum now suggests using the word forecast instead of commitment, the idea can still be abused to the detriment of the team—and the product. For example, the project manager or the clients may say that they already made their own promises, such as a release date for the marketing team, based on what the development team said it would deliver. The result: Overtime work for everyone to deliver on the original promise.

There are technology solutions around this particular problem. Pivotal Tracker, for example, makes it possible to override how long a particular iteration will be, in the number of weeks. This, functionally, allows teams to cancel a sprint altogether.

Take it from Lisa Crispin, a tester on our team, writing about the scrum concept of commitment (forecast):

"My own previous scrum team booted the commitment idea early on. It didn’t help us deliver faster or better...If you don’t have the right people, commitment isn’t going to help. But the word 'commitment' is like Mom and apple pie—it seems intrinsically good, and people think it will help the business trust the software team more. So, some companies seem to cling to the concept."

But our clients ultimately want to know when we'll be done. Instead of trying to add a layer of seriousness by calling it commitment, maintaining transparency in communications and setting visible milestones with estimated delivery dates works wonders. It also puts the onus on the team to evaluate and adjust progress toward those goals daily—instead of watching a countdown clock and scrambling to beat it.

Like Lisa says: "Our business customers don’t like hearing that a release has been delayed, but they’d rather know that weeks ahead of time instead of the day before," an especially damning outcome if the team pulled an all-nighter to sneak in under the wire.

Agile practices have seen tremendous growth in recent years, especially among enterprises. But for many organizations that have seen success embracing agile practices, these early advances have only begged the question: How do we scale this success to our entire organization? This white paper explores exactly that.